Let’s get one thing straight. Sean Lennon has absolutely no problem with who he is.

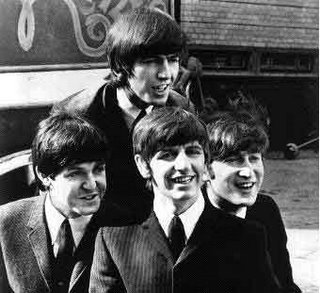

As he relaunches his music career with the bold musical brushstrokes of new album Friendly Fire, he says: “The f***ing reason I’m playing music is because of The Beatles and my dad.”

One is immediately struck by Sean’s voice. It bears a strong American accent but is shot through with the familiar, distinct nasal lilt of John Lennon.

“I can honestly say that I have a really profound relationship with every period of his work,” he says. “Every single Beatles record, every single solo album — they’re all a big part of my dad.”

He feels the records give him a relationship with his father that otherwise wouldn’t be there because, of course, “he’s not around”.

It’s touching to remember that when John sang to his “beautiful, beautiful, beautiful boy”, the world shared his joy.

His simple heartfelt ode from besotted dad to “darling Sean” appeared on Double Fantasy, the album he made with partner Yoko Ono in the summer of 1980.

Sean, I discovered, has a particular place in his heart for Double Fantasy. “I mean I was there when they were making it. I actually remember it.”

He grew up in John’s adopted home city of New York with mum Yoko and these days is part of its glamourous social whirl. While sharing his parents’ love for music, the million-dollar question has been whether he would plunge into the business big time.

Happily, I can report that if his debut album, 1998’s Into The Sun, represents a flirtation, Friendly Fire feels like a full-on commitment.

So why did he leave such a gap? “The album just happened organically,” he says. “It’s not that I was avoiding. I was doing other things. The thing is, I’m not always sure I want a pop music career. A lot of the last few years I didn’t feel I wanted one.”

Now, however, he’s even approached and subsequently joined The Beatles’ first label (Capitol in The States and Parlophone here).

“It’s a big step. I’m older and I think I’ve gotten better at music. This record is also technically better and has a much richer sound. Capitol/Parlophone seemed a more appropriate label for the kind of work I’m doing now.

I’m not a kid any more so I’m not trying to say, ‘Look how weird I am’. I’m trying to make beautiful art. It’s going to be a different career for me.

“I intentionally made my first record obscure. I mean, there’s a seven-minute instrumental jazz song in the middle of it. I wasn’t necessarily trying to make it easy for people. I’m trying to make it a bit easier this time.”

That initial reticence, you sense, might have been caused by the pressure of being John’s son but Sean says: “I have never felt the pressure.”

Yet he did give this insight: “I remember playing a show in Rhode Island as a kid and there were three fat pigs in the front row with Beatles T-shirts on and one shouted ‘Play Yesterday!’ He said it in the middle of me singing and I thought, ‘This is what everyone’s talking about’.

“But my relationship to art is not defined by some sense of foreboding about who I am. It’s like. ‘Wow, this is Dad and this is what he did.’ A lot of how I learned to play music was from listening to that stuff, and it inspires me.”

Friendly Fire is a special album. The ten songs are personal, revealing and grand in scope. Rather like many of his dad’s solo efforts, there’s a dreamlike, often childlike quality.

A key song is the title track, on which he lays bare his feelings about his split from singer-actress Bijou Phillips. Did it bother him to share his innermost feelings with the listening public?

“I have to say that I never have issues with putting out songs that are personal. I have this innate thing that I don’t care.

“What bothers me is when people don’t know how I feel but are looking at me anyway. That’s what makes me uncomfortable, being in the public eye. People are projecting this idea on to me, like, ‘I hate that Lennon kid. He should be like his dad’”.

Another great thing about the album is that ever-visual Sean has shot an accompanying film featuring all the tracks, to be released on the CD/DVD edition. When you “see” the songs, everything clicks into place.

“When I was mixing the record, I started thinking about making videos. It felt like I hadn’t finished the album until I’d finished the movie of the album. It felt like this work was supposed to continue into filming. The music is pretty cinematic sounding.”

Each song gets a different, slightly surreal setting, though perhaps not as surreal as mum Yoko would have liked. Sean says: “She was a producer and gave me advice. For a while she thought I was being too commercial but I think she loves it now.

“Her sense of film is to, say, take an avocado, film it for six days and have, like, mosquitoes buzzing around in the background. I don’t want to undermine her because I think she is probably my greatest influence, my favourite artist. But I think in her mind for a while she thought, ‘Why are you trying to do this mainstream thing?’ In the end she realised I was using that medium, the mainstream, to take people on a dreamlike journey.”

The film for opening song Dead Meat sees Sean cheat at cards and get involved in a duel. The message is that you get what you deserve in life.

He says: “When I wrote Dead Meat, I knew I had a record. It represents how my life felt at the time.

“Also, I didn’t want to do the film in a half-hearted way. The guy who’s actually fighting me taught me how to fence. I had to take about ten classes. It was a lot of work — but ultimately a lot of fun.”

A dazzling fairground ride, a rollerskating venue, a dishevelled apartment, an underwater scene and a freak show circus all feature in the album film.

“It was a roller coaster,” says Sean. “It was difficult because we only had 12 days to shoot the whole thing. We were on a shoestring budget.

“We’d do a piece one day, have three hours’ sleep and come back the next morning to a different set and have a completely new set of characters.

“The crew were p****d off but now they feel very satisfied about what we did because it was a bit over the top. People said we were crazy for trying. I didn’t even have any trailers for the crew. We were sleeping on the floor.”

The sense of sonic and visual adventure pervades all on Friendly Fire, none more so than on the film for Headlights, which has a similar feel to Ken Russell’s portrayal of The Who’s Tommy.

Sean reveals: “It was one of the easiest ones. We just had to rent this fairground ride called a Gravitron. It spins round and you stick to the wall.

“I don’t know what it’s like in England but no one here wants Gravitrons any more. The guy who rented it out wanted to give it to us. ‘Please take it,’ he said. It was just sitting in the junkyard and we turned it on and it was literally like, brrrrrrr, and these lights came on. I thought, God, this is going to be good because it’s an amazing thing.”

I ask Sean if we’ll see him in Britain, touring his new songs with a band. “Yes,” he replies, “though I don’t have a permanent staff or anything, waiting for a call. Everything depends on the tour.”

Finally, we return to a subject so close to Sean’s heart — John Lennon and The Beatles. Is he bothered what the people who have a close relationship with their incredible music think of him?

“I understand that because they’re so attached to that great music that they don’t want me to f*** with their relationship with it or mess with their idea of this perfect thing.

“But I’m not really doing it for them and I’m not trying to please them anyway. I’m doing my own thing and they can take it or leave it.”

When Sean’s album goes on sale next week, my advice is: Take it, don’t leave it.

http://www.thesun.co.uk/

article/0,,2006140003

-2006450280,00.html

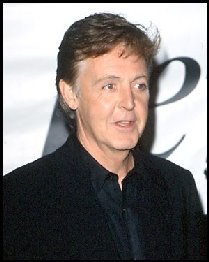

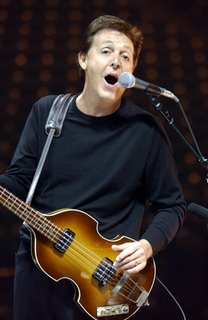

Former Beatle Paul McCartney sought on Friday to cash in on his name by registering it as a trademark for use on everything from waistcoats to vegetarian food.

Former Beatle Paul McCartney sought on Friday to cash in on his name by registering it as a trademark for use on everything from waistcoats to vegetarian food. The piece, commissioned by fellow band member George Harrison in 1973, was displayed at Takashimaya to mark the opening of a new Asprey store.

The piece, commissioned by fellow band member George Harrison in 1973, was displayed at Takashimaya to mark the opening of a new Asprey store. The tourists took a stroll around McCartney's grounds, videotaping McCartney's home and cars after entering the property from a public foot trail nearby, the Daily Mirror reported.

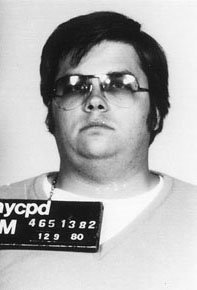

The tourists took a stroll around McCartney's grounds, videotaping McCartney's home and cars after entering the property from a public foot trail nearby, the Daily Mirror reported. Mark David Chapman, the man who murdered John Lennon, was denied parole on Tuesday (October 10th), for the fourth time. Chapman, who is now 51, is currently serving a 25-years-to-life sentence in New York's Attica Correctional Facility, for killing Lennon outside the musician's New York City apartment on December 8th, 1980.

Mark David Chapman, the man who murdered John Lennon, was denied parole on Tuesday (October 10th), for the fourth time. Chapman, who is now 51, is currently serving a 25-years-to-life sentence in New York's Attica Correctional Facility, for killing Lennon outside the musician's New York City apartment on December 8th, 1980.

Everybody needs a little love sometimes. Despite Paul McCartney's ongoing divorce battle with Heather Mills, his daughter Stella lifted the music icon's spirits on Thursday with a reassuring hug at one of her fashion shows.

Everybody needs a little love sometimes. Despite Paul McCartney's ongoing divorce battle with Heather Mills, his daughter Stella lifted the music icon's spirits on Thursday with a reassuring hug at one of her fashion shows.

A "new" album of Beatles music mixed by their legendary producer George Martin and described as a new "way of reliving the whole Beatles musical lifespan", will be released in November.

A "new" album of Beatles music mixed by their legendary producer George Martin and described as a new "way of reliving the whole Beatles musical lifespan", will be released in November. The fashion designer Jenny Kee has disclosed that she slept with John Lennon when she was 17 after the singer declared that he had never been with an Asian girl.

The fashion designer Jenny Kee has disclosed that she slept with John Lennon when she was 17 after the singer declared that he had never been with an Asian girl.

It takes exactly 20 seconds of Sean Lennon’s new album to reveal his biggest problem in pursuing a pop career — he sings exactly like his father. The reedy, nasal vocal is pure John. The gentle rasp when he extends his range is pure John. Even the pronunciation — “loovin’ you” — suggests a Scouse upbringing. Which is weird, because Lennon was born and raised in New York City, was five when his father died, and went to boarding school in Switzerland, which is generally a Scouse-free zone.

It takes exactly 20 seconds of Sean Lennon’s new album to reveal his biggest problem in pursuing a pop career — he sings exactly like his father. The reedy, nasal vocal is pure John. The gentle rasp when he extends his range is pure John. Even the pronunciation — “loovin’ you” — suggests a Scouse upbringing. Which is weird, because Lennon was born and raised in New York City, was five when his father died, and went to boarding school in Switzerland, which is generally a Scouse-free zone. A previously unreleased duet between George Michael and Sir Paul McCartney will finally see the light of the day on a forthcoming greatest hits album. Michael's Twenty Five collection is scheduled for release in November (06) and will feature the McCartney track Hear The Pain. The Careless Whisper singer's greatest hits collection, which comprises hits from his Wham! and solo career, will also feature a song recorded exclusively for the album called Understand. George Michael began his full European tour in Barcelona last Saturday (23SEP06) - his first series of live shows in 15 years.

A previously unreleased duet between George Michael and Sir Paul McCartney will finally see the light of the day on a forthcoming greatest hits album. Michael's Twenty Five collection is scheduled for release in November (06) and will feature the McCartney track Hear The Pain. The Careless Whisper singer's greatest hits collection, which comprises hits from his Wham! and solo career, will also feature a song recorded exclusively for the album called Understand. George Michael began his full European tour in Barcelona last Saturday (23SEP06) - his first series of live shows in 15 years. Sean Lennon has hit out at critics who expect him to be exactly like his dad, the late Beatle John Lennon.The young musician, who is preparing to release his new album Friendly Fire, resents expectations that he should make the same music as his late father.He says, "What bothers me is when people don't know how I feel, but are looking at me anyway. That's what makes me uncomfortable, being in the public eye. People are projecting this idea on to me, like, 'I hate that Lennon kid.

Sean Lennon has hit out at critics who expect him to be exactly like his dad, the late Beatle John Lennon.The young musician, who is preparing to release his new album Friendly Fire, resents expectations that he should make the same music as his late father.He says, "What bothers me is when people don't know how I feel, but are looking at me anyway. That's what makes me uncomfortable, being in the public eye. People are projecting this idea on to me, like, 'I hate that Lennon kid.

Paul McCartney says he's "doing fine," despite the turmoil surrounding the breakup of his marriage. McCartney, who appeared Monday at a news conference to launch his new classical album, "Ecce Cor Meum (Behold My Heart)," did not comment directly on his split from his second wife, Heather Mills McCartney.

Paul McCartney says he's "doing fine," despite the turmoil surrounding the breakup of his marriage. McCartney, who appeared Monday at a news conference to launch his new classical album, "Ecce Cor Meum (Behold My Heart)," did not comment directly on his split from his second wife, Heather Mills McCartney.