Brian Epstein, the man who discovered the Beatles and shaped them into the biggest music sensation of the 20th century, died 40 years ago at age 32. The pivotal role the enigmatic and charming Epstein played made him the world’s most admired band manager. But outside of music circles, his name is fast being forgotten.

During his lunch break on November 9, 1961, Brian Epstein—the 27-year-old Jewish proprietor of Liverpool’s popular North End Music Store—walked the 250 steps from his shop, through an alley and down the 18 stone stairs to a local cellar club appropriately called the Cavern.

Passionate about classical and Broadway music, Epstein had paid little attention to the city’s burgeoning teenage beat scene until, as legend has it, October 28th. A customer named Raymond Jones had come into his shop asking for the single “My Bonnie,” by a band called the Beatles. A few days later, a gaggle of girls had made the same request. Epstein was puzzled: There was no such record available from any British label. After some digging, he’d found that the record had been issued in Germany. The band was not credited anywhere on the disc but it was available as an import. He’d been surprised to discover that the group was from Liverpool and was, coincidentally, playing at a nearby club on Mathew Street.

When Epstein and his assistant Alistair Taylor arrived at the Cavern that day, they were the oldest guests and certainly the only ones in suits.The lunchtime show had drawn in a flood of scruffy teenagers. As Epstein wrote in his 1964 autobiography, A Cellarful of Noise, the atmosphere was not at all to his liking. “Inside the club it was black and deep as a grave and I regretted my decision to come.”

The band—John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and then drummer Pete Best—were wearing black leather jackets, their hair wild and unkempt. Epstein was intrigued by what he heard but, trained in theater and fastidious in his own appearance, he was put off by the band’s primitive stage habits. “They smoked as they played, and they ate, and pretended to hit each other…. But they gave a captivating and honest show and they had very considerable magnetism. I loved their ad libs and was fascinated by this, to me, new music with its pounding bass beat and vast engulfing sound.”

During a break, Epstein poked his head into the tiny room next to the stage, introduced himself and Taylor, and complimented the band. Harrison looked up and smiled. “Hello there,” he said dryly. “What brings Mr. Epstein here?” Harrison called over his band mates, all of whom were delighted that Epstein had enjoyed the music. They recognized him from the record shop, where they liked to hang out between gigs.

Epstein invited the band members to his shop on Whitechapel Street for a “chat” on December 3rd. In the intervening weeks, he sold over 100 copies of “My Bonnie.” When the Beatles arrived, he announced in his soft-spoken way: “Quite simply, you need a manager. Would you like me to do it?”

While Epstein had no experience as a band manager, he had the intuition of a natural businessman. He sensed that the appeal the boys possessed had enormous potential. The Beatles were thrilled when he offered his services. He promised to secure higher performance fees for their shows, extricate them from their German record contract and sign them with a British label. The Beatles were particularly impressed when Epstein assured them that he would not interfere with their music. Impatient for success outside Liverpool, it was Lennon who was the first to commit: “Right then, Brian, manage us. Where’s the contract? I’ll sign it.”

Epstein was only six years older than Lennon, the band’s self-styled leader, but to the Beatles, young men from the working class, Epstein was from a different world. The Epstein family was one of the most prominent Jewish families in Liverpool, residing in the genteel suburb of Childwall where, it’s been said, “doors had silver letterboxes and a ding-dong bell would chime and an aproned maid would answer it.” Elegant with his swank accent, Epstein wore pinstriped suits with silk cravats and drove a luxury Zephyr Zodiac. “We thought he was some very posh rich fellow,” Harrison said in the 1995 documentary The Beatles Anthology. To Lennon, “He looked efficient and rich,” and, McCartney: “We were very impressed by anyone in a suit or with a car.”

Some of their parents weren’t so easily won over. “Olive Johnson, the McCartney family’s close friend, received a call from [Jim] McCartney in a state of some anxiety over his son’s proposed association with a “Jewboy,” according to Philip Norman’s 1981 biography, SHOUT! The Beatles in Their Generation.

Epstein met with each family individually, and soon the parents were as pleased as their sons. “My Dad, when he heard about Brian wanting to manage us, said, ‘This could be a very good thing,’” McCartney said in an interview with producer Debbie Geller for a 1998 BBC documentary called The Brian Epstein Story. “He thought Jewish people were very good with money. This was the common wisdom. Dad thought Brian would be very good for us. He thought Brian was very sensible, very charming. He was right.”

Brian Samuel Epstein was born on September 19, 1934, on Yom Kippur to Harry Epstein and Malkah “Queenie” Hyman. (Malkah means queen in Hebrew.) Two years later, Queenie gave birth to another son, Clive. By all accounts, the Epsteins had a loving home. “It looked in those days that the Epsteins were a golden family, quite like a fairy story,” Harry’s sister Stella Carter once mused.

Harry and Queenie were both children of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Harry worked with his father, Isaac, in the family’s I. Epstein & Son. It was a lucrative business and the Epstein house at 197 Queens Drive in Childwall was spacious and comfortable, with a front lawn, a back garden and a garage. Inside there was rich wood paneling, stained glass, two bathrooms and five bedrooms, each with a mezuzah on the doorpost.

Although Harry kept the store open on Saturdays, the Epstein family was observant. “On Friday nights she [Queenie] lit the Sabbath candles and Harry said prayers,” wrote the late Ray Coleman, author of the 1989 biography Brian Epstein: The Man Who Made the Beatles, who interviewed Queenie before her death in 1997. “In the kitchen, the milk and meat dishes were separated, as were the cutlery and crockery. Jewish dietary rules were observed.”

The Epsteins were members of an Orthodox shul—Greenbank Drive Hebrew Congregation—where Brian and Clive attended cheder on Sundays for religious studies and to learn Hebrew. When it was discovered that Epstein had been taught the wrong parsha for his bar mitzvah, he quickly mastered the new one. “He was obviously well educated in Hebrew and Hebrew liturgy,” an uncle told Debbie Geller, who, in 2000, also published In My Life: The Brian Epstein Story, a collection of interviews about Epstein. After the bar mitzvah a reception was held at the house with over 100 guests. As a gift, Harry enrolled Brian as a synagogue member in his own right, and later did the same for Clive.

Michael Swerdlow, who belonged to the congregation, says that he admired the smartly dressed Epstein men when they arrived at services: “I recall Harry Epstein attending on high holy days and being followed into the synagogue by Brian and Clive, wearing bowler hats, which was quite fashionable for British synagogue goers to wear.”

Harry Epstein helped support the synagogue, and the family’s reputation was one of financial and social solidity. “Whenever I saw the Epstein family, they looked just like a very Jewish family, the kind I would see in the Bronx or Miami Beach,” recalls Nat Weiss, who was later to become one of Brian Epstein’s closest friends and a business partner. “Their values were very Jewish.”

Unfortunately for Epstein—who preferred the arts to sports and academics—much of his childhood was not spent in Childwall but in expensive single-sex boarding schools that children of his class were expected to attend.

At age 10, he enrolled at the prestigious Liverpool College. “Brian was rapidly convinced that there was an anti-Semitic strain running through it,” wrote Coleman. The school insisted that Brian attend school activities on Saturday mornings, which prevented him from going to synagogue with his father. Another Jew who studied at Liverpool College, Brian Wolfson, has said that the culture of the school wasn’t anti-Semitic, but “there were 600 boys, a half dozen Catholics and 25 Jews. Life wasn’t easy,” especially for a sensitive boy like Epstein.

Later Queenie and Harry decided to send him to Beaconsfeld School, a Jewish boarding school. “This I enjoyed a little better and I took up horse-riding and art, both of which I did pretty well,” Epstein recalled in his autobiography. “I began to feel more at evens with the world and I made friends with a horse called Amber, who got on very well with Jews and didn’t care that I’d been expelled from Liverpool College.”

Epstein flourished in acting and painting, and at one time wanted to be a dress designer, a calling his parents discouraged. With mediocre grades, however, he couldn’t get into a top school like Eton, and attended what was called a “minor” public school. “Naturally, my first term at public school was slightly marred by the ragging—being a Jew and not showing a great keenness for sports, the boys had good enough reason for my persecution,” Epstein wrote.

His school experience left an indelible mark on his psyche, according to Rex Makin, a Queens Drive neighbor. Makin—president of the Stapley Home for Aged Jews in Liverpool while Harry was treasurer—told Geller he believed that these anti-Semitic experiences at school left Epstein ambivalent about religion and gave him “an inferiority complex.” But Epstein would emerge from his formative years with a perspective on life that set him apart from most Liverpudlians. As Geller observes, being Jewish was an important factor in Epstein’s makeup. “It meant he was an outsider who appreciated the importance of transcending society’s view.”

Life on the stage was Epstein’s dream but he was destined for the family business. “I am the elder son—a hallowed position in a Jewish family—and much was to be expected of me,” he wrote. “My father… naturally sought in me some sign of an adequate heir to the family business, but alas, he scarcely saw a sign of any quality at all beyond a loyalty to the family, which, thanks to the steadfastness of my parents, has never faltered.”

In 1950, at age 16, Epstein dropped out of school to join his grandfather and father at the store on Walton Road in Liverpool. I. Epstein & Son was a proper, even stuffy establishment that outfitted households throughout the region. Young Epstein brought a fresh eye to the business that at first may have aggravated his grandfather but, as it turned out, he had quite a talent for display work and interior decorating, making him an ideal furniture salesman. Epstein possessed a reassuring and persuasive manner that convinced customers to “trade up” in quality and quantity.

At 18, Epstein was called up for the mandatory two years of National Service in the British military. It was a miserable experience for him. Although he excelled at clerical duties, he was a disaster in field situations. He hated the regimentation of army life, but was disappointed he hadn’t been promoted beyond the rank of private. After returning to his barracks in London’s Regent’s Park one evening dressed in his normal civilian attire—suit, bowler hat and umbrella—Epstein was mistaken for an officer and found himself facing a trumped-up charge of impersonating one. The army sent him to several psychiatrists and finally came to the conclusion that he just wasn’t soldier material. Epstein was relieved when he was given a medical discharge in January 1954.

Back in Liverpool, he worked at the furniture store by day and enjoyed the life of a bon vivant by night. He and his childhood friend Joe Flannery loved to go to the theater and see music shows, except on Friday nights when Epstein joined his parents and brother for Shabbat dinner. “One time Vivien Leigh came to Liverpool to play at the Royal Court for two weeks in A Streetcar Named Desire, and we booked the same two seats for every night,” Flannery says. “On the Friday night Brian wasn’t with me and Vivien Leigh took the trouble to put her foot through the footlights and lean over the stage and ask, ‘Where is your friend tonight?’ I said, ‘It’s Friday night and you should know,’ and she said, ‘Yes, that’s right.’”

“Brian had no qualms about being Jewish,” says Flannery, who knew the Epsteins well. Though Flannery was raised Catholic, Harry Epstein used to teasingly call him “Yossel,” Yiddish for Joseph. He and Epstein would meet for lunch regularly as Flannery worked at his own family’s store just down the street from I. Epstein & Son.

The two friends had long talks and sometimes discussed Epstein’s sexual attraction to men. In an era during which homosexual behavior was not just controversial but illegal in England, the young man felt tortured by his feelings and the situations in which he found himself. In those years gay relationships had to be cloaked in secrecy, especially in Liverpool explains Flannery.

“It was after the army that I found out about the existence of the various rendezvous and homosexual ‘life,’” Geller quotes from Epstein’s diaries. His predicament was made worse by the fact that he gravitated to a rough crowd. On more than one occasion he was involved in scuffles that left him bruised and bleeding. “All the time that I knew him, I don’t think one could say that he ever had any proper long-term emotional relationship,” Flannery says. “The people he was attracted to were not the kind of people you settle down with. He wasn’t comfortable about the fact that he was gay and, therefore, that led to a situation where he couldn’t have a successful homosexual relationship. That inability came from the fact that being gay was not his ideal way of living his life, subconscious, as that may have been. I don’t think that was unusual for his time.”

Epstein’s homosexuality added another dimension to his Jewish sensibility of being an outsider. “At no time did he want to be notorious for being gay,” says Weiss. “It wasn’t a crime to be a Jew. But it was a crime to be a homosexual.”

Life in Liverpool became stifling. In 1956, Epstein convinced his father to give him leave from the business to attend the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in London. His contemporaries included such performers as Susannah York, Peter Blythe, Peter O’Toole, Albert Finney and Joanna Dunham. While Epstein was a respectable actor, he realized that he would never advance beyond secondary roles. He did not return for the fall term, ending what then seemed to be another dead-end venture outside the family business.

Rather than send Brian back to armchairs and cocktail tables, Harry teamed him with Clive for a new spin-off business, North End Music Stores (NEMS), devoted to domestic and electronic goods. Clive was responsible for the hardware department, including washing machines and radios. Brian was put in charge of the record section. He was responsible for the selection, purchase and in-store promotional display of recordings from all genres. He developed a keen ear for anticipating pop music hits and ordering stock accordingly. In short order NEMS became the place in Liverpool to find music and the store developed a reputation for unrivaled customer service. This included “listening booths” that allowed customers to preview discs before purchase, which made the well-stocked NEMS stores a favorite teen hangout. Young fans could commandeer a booth and sample the latest releases. It was also NEMS policy to guarantee to provide any record that a customer requested. And it was this promise that led Epstein to take notice of the local group with the odd name playing in the club down the road.

Now a confident businessman, he was looking for a bridge that would bring him back over to the artistic world. His sights were set on a life beyond Liverpool: He just hadn’t yet worked out how to get there. In some ways, says Geller, his vision of a better life was a legacy of his Jewish upbringing. “He reflected the attitude of Jewish immigrants that each generation would become more successful. They would look to America, especially New York, with a bit of envy; success there became a goal. This was especially true in show business. America had its own kind of glamour. Epstein was not provincial. He was cosmopolitan. Local success was not enough for him. He could envision more.”

The little-known band and its first-time manager had found each other at the perfect time. The Beatles had reached the glass ceiling for rock ‘n’ roll bands in Liverpool. In Eppy, as they called him, the Beatles had found a manager with integrity and honor, primed to devote himself to their success in a way no one else could.

“Brian fused everything,” says Nat Weiss. “The Beatles were together before they met Brian and they had the talent. But it was Brian who was the emotional and psychological catalyst. He had the vision to say that the Beatles would be bigger than Elvis in 1961.”

Epstein treated his band with respect; in return, they listened to him. “He was in charge and they did what he said,” George Martin, the man who would later become their producer, told Geller. “I mean, he was their only hope.”

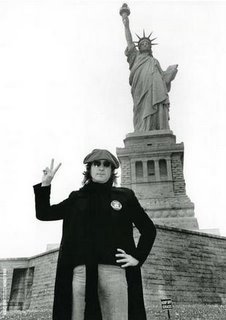

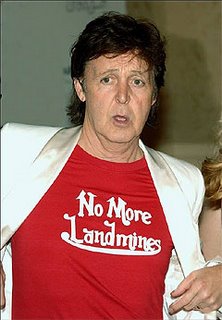

His first task was to recast their image. He had their hair styled, and took them out of the leather jackets and put them into finely tailored mohair suits. On stage, he insisted that they look and act like professionals. They started showing up to gigs on time, stopped drinking and smoking on stage, began to play from a set song list and added an endearing polite bow in unison at the end of each performance. “I think the [RADA] theatre training—and Brian’s immersion in pop at the record store—is what made him aware of the potential for the group—style, clothing and so on,” says Alan Swerdlow, a friend of the Epstein family.

Next, Epstein began making trips to London to pitch the Beatles to record companies. But landing a record contract was a formidable challenge. Epstein had to convince the major labels in London to even consider looking at Liverpool for talent. “It was Epstein’s credibility as a major record retailer that got anyone to give him the courtesy of a listen at all when he was first trying to get the Beatles a contract,” says Geller. “His retail business was important to them.”

The Beatles were rejected by nearly every major label. “The boys won’t go, Mr. Epstein,” Epstein recalled Decca executives telling him. “We know these things. You have a good record business in Liverpool. Stick to that.” Only his polished manner and persistent follow-up kept the process going.

“John and I used to wait at Lime Street Station in a little coffee bar called the Punch and Judy,” Paul McCartney told Geller. “We used to wait for Brian arriving back from London, and when he’d come in we’d take a look at his face to see if the news was good or bad, and it was bad. It was always bad. He’d be, like, ‘Sorry.’ We’d go, ‘Oh,’ and we’d have a cup of coffee and discuss what had happened. He would just say, ‘You know, people aren’t generally interested. You know, it’s going to be a hard sell.’”

But Epstein wasn’t so easily dissuaded. Nerve-wracking as the search was, he continued his pursuit, all while maintaining his responsibilities at NEMS.

Although they were as supportive as usual, his parents were afraid that their eldest son, having finally become a responsible businessman, was foolishly risking his career on behalf of four non-entities. They were troubled by his foray into Liverpool’s raucous and less-than-respectable music scene. Their concern was warranted. Epstein’s intense commitment to the Beatles did have its dark side according to Epstein friend and business associate Peter Brown. “This is when he started taking amphetamines,” Brown told Geller.

The Beatles got their big break when Epstein was introduced to the music publisher for EMI Company at a record shop in London. Although the group had already been rejected by three of the four main labels at EMI, the publisher—Sid Coleman—directed him to George Martin, the producer and A&R [artist and repertoire] director of the fourth and smaller jazz and comedy label—Parlophone. Martin was impressed with the young manager. “[Epstein] certainly wasn’t cast in the mould of hardened professional. He seemed to be a little bit ingenuous but he was fresh,” Martin has said. “I liked him. I thought he was good and I was persuaded by his enthusiasm.” This meeting led to the Beatles’ first test recording session on June 6, 1962, less than six months after Epstein had signed on as their manager.

Martin liked what he heard and offered to sign them, with one proviso: He felt Pete Best’s drumming wasn’t up to par and planned to use a studio drummer. That clinched a growing desire by Lennon, McCartney and Harrison to replace their band mate, and they left it to their manager to deliver the news. On August 16, 1962, Pete Best was out and Ringo Starr, the drummer for another popular Liverpool band—Rory Storm and the Hurricanes—was in.

The Beatles, as we know them, recorded their first single the following month. On October 5, 1962, Parlophone released “Love Me Do.” Brian Epstein and the Beatles began their wild ride. After years of dreaming, the five young men stepped together into a film running on fast forward. When “Love Me Do” reached number 17 on the British charts, they were overjoyed.

Throughout 1962 and in the first months of 1963, the band toured Britain nearly nonstop, with every detail meticulously planned by Epstein. “There was a touch of a parent’s pride as they grew,” says Geller. “He was very much part of that growth, especially in the early days of touring both in Britain and in the United States. He was always there for the shows, usually standing off at one side of the stage.”

Though he’d gotten himself closer to the stage, Epstein could still only circle the spotlight. “Brian was a failed creative person,” says Geller. “The Beatles were successful performers. Brian envied that; he was a wistful admirer. He wanted to be an artist, not a manager. But he also had the self-awareness to see the difference between what you can do and what you’d like to do. He chose what he could do. He propelled them.”

Sometime alongside this flourishing business relationship, a deep personal bond had formed between Eppy and his boys. In 1962, Lennon’s girlfriend, Cynthia Powell, became pregnant. Aware that the band’s appeal depended in part on the “availability” of its members, Epstein quietly arranged the wedding and gave them his flat in Liverpool. When Julian Lennon was born, Epstein was named his godfather, and would later be best man for both Harrison and Starr.

“We all liked him,” Cynthia Lennon has said, “because he was so obviously genuine. He had a sunshine face, manners and was very sweet, a gentleman. He was much older than us mentally. I held him a little in awe because I’d never met ‘a Brian’ before. He had life all sussed out, it seemed to us. He had suits and ties that matched.”

Although Epstein never played favorites, he had a clear affection for John. There are lingering rumors that he was in love with Lennon and that their relationship was consummated during a vacation the two took together in Spain shortly after Cynthia gave birth to Julian. Most friends, including other Beatles, have said that this is simply untrue. Lennon was a confirmed heterosexual, and Epstein wouldn’t have crossed professional boundaries.

Lennon was a captivating man and it is not outside of the realm of possibility that Epstein was physically attracted to him, says British rock journalist Steve Turner, author of the forthcoming The Gospel According to the Beatles. “Epstein liked rougher people, he liked being taunted and being treated in a cruel way,” he says. “There was something in him that drove him to this: Maybe he came to see abuse as something that he deserved. John did have that kind of wicked way of talking.”

Lennon was known for biting remarks made at everyone’s expense, and he did not spare Epstein, whom he is said to have admired and liked greatly. “‘In Baby You Are Rich Man,’ Lennon is reported to have sung ‘Baby you are rich fag Jew’ at the end of the record,” says Turner. There were other such jibes over the years but Lennon, wrote Coleman, may have been the Beatle who truly grasped the extraordinary qualities in Epstein that made him the driving force behind the group. “Epstein put up with Lennon’s remarks. Anyone working with Lennon learned to live with his caustic tongue.”

In February 1963, the Beatles second single “Please Please Me” hit number one and the following month their first album began its 30 week stint at the top of the charts. Fame was quick to follow. “It happened suddenly and dramatically,” wrote Epstein, “And we weren’t prepared for it.”

On November 4, 1963, the band received its highest recognition to date: An invitation to play for Queen Elizabeth and her family at the annual Royal Command Performance. Deferring to Epstein’s judgement, Lennon agreed to clean up a planned humorous remark directed at the royal family in which he invited them to rattle “your jewelry” rather than your “fucking jewelry.” The expletive-free version went over well and the band was a hit. Princess Margaret was smitten.

The Beatles now had broad appeal throughout Britain. “Without Brian the Beatles never get out of Liverpool,” says Glenn Frankel, a Washington Post reporter who is researching Epstein’s life. “Liverpool was a small subsidiary of the Empire. It was Podunk and people in London looked down their noses at Liverpool talent. There was no way to get from here to here to there. Without Brian they could have been Michelangelo but they didn’t get out. Without Brian, they were just the best band in Liverpool.”

In less than one year, the Beatles went from releasing their first record to being the number one act in England. The British press coined the term “Beatlemania” to describe the fanatic reception the group received in public. Epstein’s role for the group took on a new aspect. It was only a few months ago that Epstein was knocking on all doors to sell the Beatles. Now, he was their first line of defense, guarding them from incessant press exposure and mobs of excited fans. Under his watchful eye, Epstein guided the “Fab Four” through the whirlwind they were creating.

During it all, Epstein transformed NEMS into a full-fledged talent management company, hired a staff and signed on other talented Liverpool artists such as Gerry and the Pacemakers and Cilla Black. Elvis Presley’s manager, Col. Tom Parker, found it astounding that Epstein found the time to manage more than one major group. But no matter how many artists Epstein had to juggle, the Beatles were always his first love.

Epstein had his eye on America but his connections were limited to the United Kingdom. In the autumn of 1963, New Yorker Sid Bernstein called him at home in Liverpool to ask if the Beatles might be interested in playing Carnegie Hall. Bernstein was a music business student at the New School for Social Research and while he hadn’t heard the group’s music, he’d studied British newspapers for class. Mention of the Beatles had simply been impossible to miss.

Bernstein offered Epstein $6,500 for two shows and Epstein was impressed. According to Coleman, he couldn’t wait to tell his friends at Isow’s, a Jewish restaurant in London’s Soho district where agents socialized. For Bernstein, it was always a pleasure to do business with Epstein. “Once he gave his word he never changed terms or renegotiated.”

The two made deals on the phone, not relying on written contracts. “It was like a handshake on the phone. He just had that kind of quality, you believed him, you trusted him. That isn’t true of very many people in the business. My experience has taught me that it is very few and far between that you find someone like Brian.”

Bernstein and Epstein planned the concerts, and in November, Epstein flew to New York and arranged the three now-famous Beatles appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show. Their first show still ranks as one of the most viewed programs on American television ever. By the end of 1964, the Beatles had replicated their British success in the United States and were the top performers in the nation. “Not only did he get them to the United Kingdom,” says Frankel, “He got them to America. No British pop act had ever succeeded in doing that. They were the first to cross over.”

Now that the Beatles were a worldwide success, the time had come for all five men to leave Liverpool. NEMS moved into flashy new offices near the London Palladium. Epstein bought a townhouse at 24 Chapel Street in Belgravia.

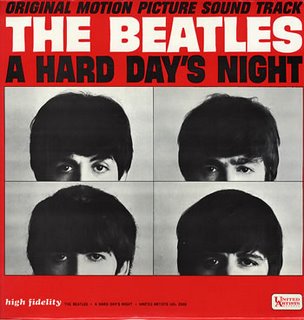

It was a heady time for Eppy and the boys. London in the ’60s was a happening place and the band fit right in. They released films such as A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, and in 1965, they were knighted as Members of the British Empire (MBE). Epstein simply glowed when the Beatles received their MBEs and Paul McCartney announced that MBE really stood for “Mister Brian Epstein.”

Some have speculated that Epstein believed that he was excluded from the honor because he was a homosexual and a Jew, but most say he never expected to be knighted. By now Epstein was a secular Jew who was observant only when in the company of his family, but he never hid his religion. “Once in a while people would make a remark that was anti-Semitic,” recalls Weiss. “He would say, ‘I am Jewish.’ He spoke out against anti-Semitism. He’d get very angry. He was against all prejudices.”

As the Beatles matured musically in the studio, Epstein arranged ever-larger venues for their live shows. Stops on the 1966 international tour in Japan and the Philippines were especially exhausting, marred with misadventures that were out of Epstein’s control. It was, however, the U.S. segment of the tour that threatened to be dangerous.

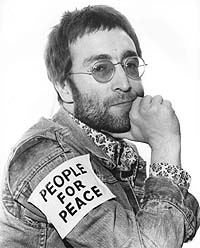

It all started with a Lennon interview that made American headlines right before the Beatles were due to arrive in the States. “Christianity will go,” Lennon had said while discussing the state of world religion with a reporter from the London Evening Standard. “It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue with that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first, rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

Lennon’s words set off a storm of outrage in the United States. Demonstrators burned Beatles albums and Epstein was afraid that Lennon would be assassinated. “After Lennon made those remarks,” recalls Weiss, “Epstein wanted to cancel the whole tour, I met him at the airport and he asked me how much it would cost to cancel. I said about one million. He wanted to pay it. He didn’t want anything to happen to them and for them to be exposed to violence. And he wanted to make sure that anyone who had invested in the tour wouldn’t lose money.” The tour went on, stopping at stadium venues from Chicago to San Francisco.

When the Beatles came home they decided to exclusively focus on studio recording and went to work on one their seminal albums—Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Epstein loved touring and was disappointed by the band’s decision, but ever supportive, he helped launch the album with a party at his London residence.

Epstein was the glue that kept the foursome focused as they redefined popular music. “The Beatles followed him and believed in Brian,” says Bernstein. “He handled himself so beautifully and reduced what might have been huge problems to ‘Let’s get on with it, boys,’ and they did. It’s always tough keeping a group together. Each band member has their own problems and multiply it fourfold. But he kept them together, unified and they followed his recommendations to the letter.”

Even without touring, there was more than enough to keep Epstein busy. “There were so many deals, important deals,” says Bernstein. “His phones never stopped and the proposals given to him were of an enormous, enormous nature and enormous amounts of money.”

In hindsight, Epstein has been criticized for failing to secure the most lucrative deals for the Beatles during the 1960s. “It was a different era,” says Turner. “Bands today realize that they can make as much money from T-shirts, programs and spin-off products. But in those days, they didn’t know it.” Epstein was one of the first band managers to deal with merchandising contracts. “He really almost gave stuff away.”

Overall, the Beatles were pleased with Epstein’s management style and understanding of his shortcomings. “The problem arose because… he hadn’t done this kind of business before,” said Paul McCartney in In My Life. “He had a great theatricality. But I think some of the deals he got us were great for the time but not so great, it turned out.… I think for what he knew and for what he could bring us, he was really excellent, and I don’t think the Beatles would have been the same without him.… He was the director. That’s what he really was.”

Epstein’s value to the Beatles could not be measured by money, says Weiss: “I don’t think that what the Beatles needed was a great businessman. They needed a person who would inspire them, whose neurosis was sufficient for him to identify with them. And for Brian the Beatles were an alter ego. Brian was on stage with those Beatles emotionally and he devoted his life to them.”

The pressure of staying on top of the music world was relentless. The pill-popping habit that began when Epstein was first pitching the Beatles grew worse. He became dependent on sleeping pills and suffered from insomnia, depression and excessive irritability. He would take drugs to stay up at night and sleep away the day.

Despite Epstein’s manic hours and drug abuse, he made sure to pull himself together when he visited with his family, says Weiss. He remained especially close to his mother. “She had great taste and he had great taste. She was a very sophisticated lady, almost aristocratic in her bearing.” Mother and son discussed everything, including his relationships with men and her hope that he would one day get married. Joe Flannery says that Epstein “was also attracted to ladies, and I am saying ladies, and they were attracted to him. There was one, Alma Cogan [born Alma Angela Cohen], a huge star in the 1950s. He was very fond of her and she of him. Remember, he was very young. He was very busy and he didn’t really have any time for long-term relationships. If he hadn’t died he probably would have had a [long-term] relationship [with a man] by now. And a wife.”

On July 7, 1967, Harry Epstein died at the age of 63. Brian Epstein was at Queenie’s side within hours of the death and made the arrangements. “The loss of his father shattered Brian,” wrote Coleman. “The years of pre-Beatles misunderstanding had been replaced by Harry’s pride in his eldest son’s achievements and fame. On the return from the cemetery to the new Epstein home in Woolton, he sobbed uncontrollably in the car.”

Epstein stayed with Queenie at her house during the week of shiva. Away from the world of the Beatles, he found time for reflection. “My father’s passing has given me the added responsibility of my mother,” he wrote his friend Nat Weiss. “The week of shiva is up tonight and I feel a bit strange. Probably been good for me in a way. Time to think and note that at least now I’m really needed by Mother. Also time to note that the unworldly Jewish circle of my parents’ and brother’s friends are not so bad. Provincial, maybe, but warm, sincere and basic.”

For the next three weekends Epstein traveled to Liverpool to be close to his mother. When he was away he phoned her every night, and on August 14th, she came to London for a 10-day visit, during which he comforted and lavishly entertained her. “He rose at early times and went bed at a normal time, a routine refreshingly different for him,” wrote Coleman. They made plans for Queenie to move to London so that she could be near him.

Two days after she left, on August 25th, he drove up to his new five-acre 18th century country home—Kingsley Hill. He dined with friends Peter Brown and Geoffrey Ellis, and then waited for some guests he had invited for the evening. When they didn’t show, he drove back to his home in London.

The next morning several friends made calls to Epstein’s house but received no answer. When no one heard from him by evening, they became alarmed and broke down to his bedroom door. They found his body, still in bed. Next to him was a pile of open correspondence, a working script for the Beatles movie Yellow Submarine and a book he was reading, The Rabbi, by Noah Gordon.

The coroner’s report ruled his death accidental, the result of an overdose of the sedative Carbirtal. Brian’s brother, Clive, and his wife Barbara, then eight months pregnant, got the call and were the ones to break the news to Queenie. Still in mourning, she had sustained another unthinkable loss. “The poor woman was devastated at having lost her husband and son within three months,” says Weiss.

The Beatles were on retreat with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, spiritual leader and founder of the Transcendental Meditation movement, in Wales, when they were notified. “It was just like one of those phone calls: ‘Brian’s dead,’” recalled McCartney. “You just sort of went pale and immediately traipsed off to the Maharishi. We said, ‘Our friend is dead. How do we handle this?’ And he gave us practical advice. ‘Nothing you can do. Bless him, wish him well, get on with life’ kind of thing. But we were very shocked and what added to it, as it always does with celebrities, the media wanted to know how you feel and it’s always too quick… you just can’t talk about it.”

Rumors spread that Epstein committed suicide but his friends and family never believed this likely. There was no note or legal will, and Epstein had many plans for the future. Most of all, he was devoted to his mother, who needed him more than ever at the time of his death.

The family wanted a quiet Orthodox funeral at the Greenbank Drive Synagogue and asked the Beatles not to attend for fear that it would draw too much public attention. Following Orthodox tradition, only the men accompanied Epstein’s body to the Jewish Cemetery on Long Lane in Aintree. Epstein was buried near his father. “After the burial, the rabbi, who didn’t know Brian, said something about him being a symbol of the malaise of his generation, which was amazing,” says Weiss. “How can a man who filled stadiums, who literally was the catalyst for the greatest musical event of the 20th century, be treated as a malaise of his generation? It was such an unjust epitaph. It was disgusting.”

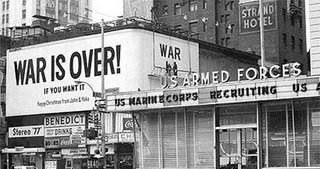

Six weeks later, the Beatles attended a memorial service at the New London Synagogue on Abbey Road. All four wore black paper yarmulkes. This time the officiating rabbi, Louis Jacobs, praised Epstein, “He encouraged young people,” Jacobs said, “to sing of love and peace rather than war and hatred.”

In the months after Epstein’s death, the Beatles would come to realize what they already suspected: Brian Epstein was irreplaceable. Without him, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr had no one they trusted to look out for their interests. Without Epstein’s unique combination of ethics, protectiveness and charm, they were forced to handle business details and interpersonal squabbles by themselves.

There was no obvious successor. McCartney, then engaged to Linda Eastman, supported her brother, Lee, a lawyer, for the role. (Eastman’s family was Jewish; coincidentally, Eastman was an anglicized version of their original name, Epstein.) The other was Allen Klein, an established rock manager who handled such acts as the Rolling Stones. Klein did take care of some key record company negotiations and reorganized the new company that the Beatles had formed—Apple—with the blessing of Lennon, Harrison and Starr, but McCartney never signed on.

The Fab Four began managing themselves but without their long-time mediator and polished representative, the atmosphere grew increasingly acrimonious. In his book Here, There, and Everywhere, studio engineer Geoff Emerick remembered the 1968 sessions for what became The Beatles album, most commonly called The White Album, being painfully difficult, as interpersonal tensions spilled into the studio. Viewers of the theatrical feature Let It Be, filmed during recording sessions held in early 1969, could see the tension for themselves on screen.

Even as the band identity that Epstein had so carefully crafted began to disappear, the momentum he had helped build, continued. From 1967 to 1970, the Beatles went on to produce some of their greatest music, including “Hey Jude,” their most successful single, and Abbey Road, one of their most respected albums. But the old feeling was gone. “We made a few more albums but we were sort of winding up,” said McCartney. “We always felt we’d come full circle and Brian’s death was part of it.” In 1970, less than three years after Epstein passed away, the Beatles disbanded. “After Brian died, we collapsed,” said Lennon in a 1971 Rolling Stone interview.

There are few reminders of Brian Epstein left in Liverpool. A plaque and an oil portrait hang in the lobby of the Neptune Theater, which is currently closed for remodeling. Photographs and notes about Epstein line the wall of “The Beatles Story Exhibition.”

Outside of town is the small Jewish cemetery where the Epstein family plot can be found. “It’s the saddest thing,” says Glenn Frankel, who visited the cemetery recently. “Brian had finally escaped Liverpool and was back before he was 33. Clive died of a heart attack in 1988 at the age of 51. And there is Queenie, who survived all her men and who was pretty miserable at the end of her life, having her golden family fall away.”

The epitaph on Epstein’s tombstone does not say anything about his life accomplishments. The grave is simple, says Weiss, as befits a man whom he calls a good Jew. “Brian adhered to the best tenets of Judaism, he kept to the highest values of the Jewish faith,” he says. “He was an honest man, extremely fair in his dealings. He was very compassionate and understanding of his fellow man, he believed in mercy and compassion. He was very kind and very generous. He was like a saint in that respect.”

http://www.momentmag.com/

features/aug06/

2006-08_Epstein.html

Official chart records are being changed to make former Beatle George Harrison's first solo album, All Things Must Pass, a No 1 record.

Official chart records are being changed to make former Beatle George Harrison's first solo album, All Things Must Pass, a No 1 record.