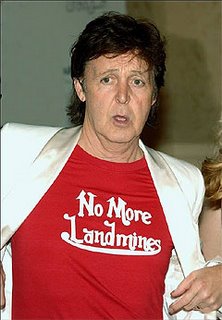

“You’ll be met at the station,” teases Paul McCartney’s publicist, “where you’ll be blindfolded and driven to a secret location.” In fact, the assistant who picks me up and drives me in her battered estate car to McCartney’s Sussex recording studio couldn’t be friendlier. No walkie-talkie earpieces or security gates to speak of (although the phrase “hidden devices” almost certainly applies), just an unkempt gravel lane winding through lawns and past rose bushes to a group of buildings high on a ridge, overlooking the English Channel. Oh, and a windmill, naturally.

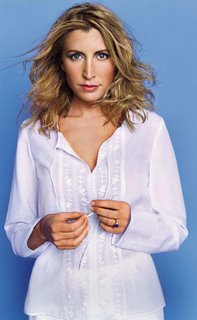

The property is a short hop from his farm, location of the infamous log cabin over which McCartney is currently in dispute with the planning officers. He is mired in certain other legal disputes, too, and the publicist is at pains to point out that questions on this are verboten. So Heather Mills- McCartney is off limits. Long may she stay that way.

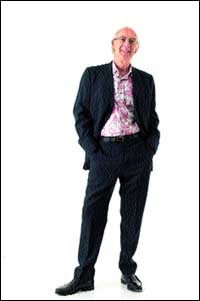

Her estranged husband, far from looking weighed down with anxiety, exudes bonhomie. It is in stark contrast to his demeanour when I last interviewed him, five years ago.

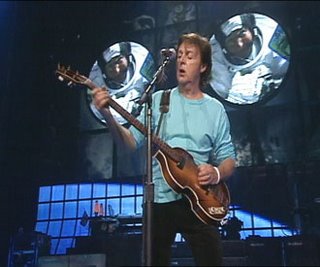

At that time, he was emerging from the deep slough of despair that had claimed him following the death of his first wife, Linda, and was gearing up for his second marriage. Tellingly, he came across then as strident, hectoring, uncomfortable in his skin; he looked old and angry. Today, he is youthful in comparison. Putting the finishing touches to a new pop album, McCartney is doing what he has always done in adversity — seeking refuge, therapy, even, in music.

The only time in his life, he says, when he found this escape route blocked was when Linda died. Music was impossible. He cried for a year. “Life beats you down occasionally,” he says, in his Liverpudlian singsong, “and when it does, you just have to not try. But I am the eternal optimist. No matter how rough it gets, there’s always light somewhere. The rest of the sky may be cloudy, but that little bit of blue draws me on.”

This is one of two points in the interview where what is unspoken hovers, clamorously, in the air. We are sitting in a huge, memento-filled room above the studio, a space filled with light and with views out to sea, above which banks of stupendous clouds scud across a sky that is luminously, unmistakably blue.

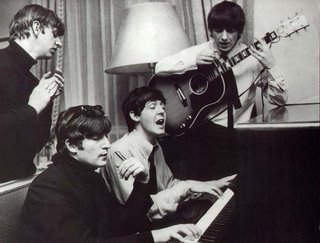

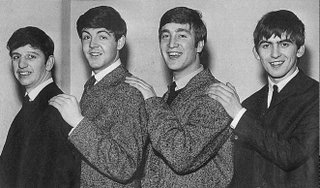

You have to keep it together in a situation such as this. When, to illustrate a story he is telling, McCartney drags his sofa closer to the one I’m parked on and begins, “Working with John, like this, him there with his right-handed guitar and me here with my left-handed one”, you feel the finger of history running its nail up your spine. Ditto when you notice that his feet, famously bare on the Abbey Road sleeve, are unshod again. It is an effort to maintain concentration.

But we can dip in and out of all this.

In June, the $170m Beatles-based Cirque du Soleil show LOVE opened in Las Vegas. Last month, it was announced that the Fab Four’s ever alert Apple Corps is suing EMI over unpaid royalties. And in the past fortnight, it has been announced that the Casbah Coffee Club, in Liverpool, where the then Silver Beatles played their first gigs, has been awarded listed status; and that postage stamps bearing the Beatles’ faces are to be issued in January. “And in the end,” they sang in the closing bars of Abbey Road. But it never did end. It goes on.

I ask McCartney if, even now, he has moments where he wants to pinch himself, where he goes: “Eh?” He says at once: “Oh, yeah.” And, in an echo of those sharp early press conferences, where the Fabs toyed with their inquisitors, putting them to the sword with Scouse wordplay and wit, he says of the stamps: “I just want to be licked.”

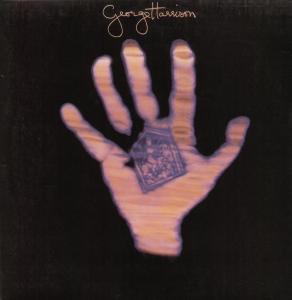

He is back in the promotional fray to talk about Ecce Cor Meum, his new work for choir and orchestra, which he began working on eight years ago. It’s his fourth classical release, following Liverpool Oratorio, Standing Stone and Working Classical. None was especially well received, but then nor were the majority of his post-Beatles solo albums, nor his paintings, nor his book of poetry. In part, this is because the Lennonists have tended to John’s shrine with, it sometimes seems, burnt offerings in the form of McCartney’s poor-relation reputation. Back in 2001, the latter spat back at these snipers. “I, particularly, took a lot of flak with John,” he said.

“The break-up, and then, of course, when John died ... very tragically. Obviously, people’s sympathy is going to go to him, including mine,” he recalls. “But the picture did get a bit muddy. People did go over the top and say, ‘Well, it was only John, the other three were just hangers-on.’ When you’ve taken so much flak, you do think, enough’s enough.”

There is no trace of that anger today. Rather, he seems sanguine, more able to accommodate the whole mad journey he was a part of. And it is clear that he sees Ecce Cor Meum as very much another stage in that journey. This insistence on continuity, on a thread linking the Beatles with Wings, with his solo career, maddens detractors. But to him it is an inescapable fact. He got “in the vehicle”, as he calls it, when he was a boy, and he is still at the wheel today.

“I love choirs,” he says, explaining the alacrity with which he accepted Magdalen College, Oxford’s commission of a new choral work. “I was in one as a kid, St Barnabas at Penny Lane. And I tried out for Liverpool cathedral, and sort of got to the last stages. But” — and here his faces creases into a delighted grin — “I was not musical enough, obviously. At school, in terms of musical education, I got zero. We’d all go into the classroom, about 30 Liverpool boys, and the teacher would put on a record — Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, something like that — then he’d leave the room. So of course we just took it off, posted a guard on the door, got the ciggies and the cards out, and when he came back, we put the record back on for the last couple of bars. He’d go, ‘What did you think of that?’ And we were like, ‘Oh, really good, sir. Fabulous.’”

Ecce Cor Meum both benefits and suffers from this lack of training. Between reeling out the lines of melody and hauling them back in for each of the four movements’ conclusions, McCartney’s writing — which he did chiefly on a synthesizer, prior to orchestrating it — can potter pleasantly, if aimlessly. His extraordinarily forensic musical ear has picked up not just the rudiments, but somehow also the vernacular of English 20th- century choral and operatic music: echoes abound of Parry, Tippett, Vaughan Williams, William Henry Harris, Herbert Howells; more globally, Berlioz and Bernstein are clear creditors. Moreover, his untrained approach can produce moments of hair-raising modulation and digression. Interlude, which divides the piece, is the most shattering example of this. Set for oboe and choir, its wordless, lulling structure was written in tribute to Linda. “I’ve played it to some people,” says McCartney proudly, “and said nothing, and I’ve seen them welling up. It’s an amazing phenomenon,” he continues quietly. “How chords can be... sad.”

Writing Ecce wasn’t just a case of not following the rules, he says; it’s never been about only that. “We didn’t know the rules. I remember in the very, very early days in Hamburg, asking Tony Sheridan what he thought of one of our songs, and he said, ‘Well, it’s just a scale.’ So much of what we did (he starts to sing)...‘Last night I said these words’; so you’ve got to go, ‘To my girl.’” Again, the finger works up the spine. “You’ve got to break it and not have it too scaley. Scales are great, they’re hooky. But then you think, ‘Okay, now let’s get away from that, let’s do the one-note thing.’ I remember when I was writing She’s Leaving Home, trying to not change the chord.” He sings again. “So, you know, it’s ‘She’s... leaving... home’, and it just stays on that chord. So then, when it lets go, it’s lovely. You get the release.”

The crude characterisations of McCartney the soppy dramatist, Lennon the visceral diarist, were always just that: partisan simplifications that obscured far more than they unearthed. It was McCartney, after all, who first experimented with tape loops (a process that bore glorious fruit in Tomorrow Never Knows); who was into Berio and Stockhausen, and part-funded the avant-garde Indica gallery, where, ironically, Lennon first met Yoko. That all this is often overlooked is, McCartney says, because of what he calls “the surface image”. “I didn’t want to shout about them, but I’d like them on the record. But it is an image thing. Mine has always been a bit sort of clean-living or whatever, until” — and here he twinkles mischievously and pauses — “... not always.”

He is, he says, beginning to be able to assess what the Beatles achieved, what they meant, what they still mean. He found the Cirque du Soleil show very emotional. “Because it’s my mates, and because of the fact that it’s no more, except on record — physically no more. In the middle of the show, I was sitting next to Ringo, I was welling up, and I just turned to him and said, ‘F***ing great band. Listen to these noises. How did we do that?’” He is still making those noises; is still, he admits, in pursuit, hearing a chord, bumping into a phrase and off he goes.

Downstairs, post-interview, he takes me into the kitchen, where a table is laid with food, and makes me a doggy bag for the train, including a slice of sponge cake.

“Excuse fingers,” he says.

Like I was going to insist on an ex-Beatle using the tongs.

Briefly, I toy with putting the cake up for auction on eBay. But you know what? I ate it instead, fingerprints and all. But I kept the napkin he wrapped it in. As you would.

A life in music

1964 Things We Said Today Macca at his most plaintive and melodically meandering on this minor-key gem from A Hard Day’s Night.

1966 Eleanor Rigby McCartney’s most evocative lyric, and a song that did justice to The Times’s famous Schubert comparisons.

1968 Helter Skelter George called his record label Dark Horse, but it was McCartney, on this White Album, Manson Family-inspiring shocker, who emerged, black as night, from the Beatles stable.

1970 Maybe I’m Amazed People say Patti Boyd inspired great love songs (Something, Layla), but Linda did too.

1975 Listen to What the Man Said One of many songs where you think: nobody else would have bothered to write a bass line this complex and this beautiful.

1982 Here Today From the great Tug of War, the first album McCartney made after Lennon was killed, a heartfelt but unblinking ode to his erstwhile friend.

2001 Blackbird Singing McCartney mixed song lyrics with poetry in this book, writing movingly about Linda.

2005 Riding to Vanity Fair A return to old wounds on last year’s Chaos and Creation album? John’s ghost haunts it.

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/

article/0,,2101-2366846_1,00.html

A previously unreleased duet between George Michael and Sir Paul McCartney will finally see the light of the day on a forthcoming greatest hits album. Michael's Twenty Five collection is scheduled for release in November (06) and will feature the McCartney track Hear The Pain. The Careless Whisper singer's greatest hits collection, which comprises hits from his Wham! and solo career, will also feature a song recorded exclusively for the album called Understand. George Michael began his full European tour in Barcelona last Saturday (23SEP06) - his first series of live shows in 15 years.

A previously unreleased duet between George Michael and Sir Paul McCartney will finally see the light of the day on a forthcoming greatest hits album. Michael's Twenty Five collection is scheduled for release in November (06) and will feature the McCartney track Hear The Pain. The Careless Whisper singer's greatest hits collection, which comprises hits from his Wham! and solo career, will also feature a song recorded exclusively for the album called Understand. George Michael began his full European tour in Barcelona last Saturday (23SEP06) - his first series of live shows in 15 years. Sean Lennon has hit out at critics who expect him to be exactly like his dad, the late Beatle John Lennon.The young musician, who is preparing to release his new album Friendly Fire, resents expectations that he should make the same music as his late father.He says, "What bothers me is when people don't know how I feel, but are looking at me anyway. That's what makes me uncomfortable, being in the public eye. People are projecting this idea on to me, like, 'I hate that Lennon kid.

Sean Lennon has hit out at critics who expect him to be exactly like his dad, the late Beatle John Lennon.The young musician, who is preparing to release his new album Friendly Fire, resents expectations that he should make the same music as his late father.He says, "What bothers me is when people don't know how I feel, but are looking at me anyway. That's what makes me uncomfortable, being in the public eye. People are projecting this idea on to me, like, 'I hate that Lennon kid.

Paul McCartney says he's "doing fine," despite the turmoil surrounding the breakup of his marriage. McCartney, who appeared Monday at a news conference to launch his new classical album, "Ecce Cor Meum (Behold My Heart)," did not comment directly on his split from his second wife, Heather Mills McCartney.

Paul McCartney says he's "doing fine," despite the turmoil surrounding the breakup of his marriage. McCartney, who appeared Monday at a news conference to launch his new classical album, "Ecce Cor Meum (Behold My Heart)," did not comment directly on his split from his second wife, Heather Mills McCartney. The 64-year-old former Beatle sent a message of support, saying it would be a "real shame" if vital services were cut back at the Conquest Hospital in St Leonards, East Sussex.

The 64-year-old former Beatle sent a message of support, saying it would be a "real shame" if vital services were cut back at the Conquest Hospital in St Leonards, East Sussex. Heather Mills is not the only one whose reputation has taken a beating in her bitter divorce battle from estranged hubby Sir Paul McCartney, for she’s now threatening to do the same for him with some “bombshell” revelations.

Heather Mills is not the only one whose reputation has taken a beating in her bitter divorce battle from estranged hubby Sir Paul McCartney, for she’s now threatening to do the same for him with some “bombshell” revelations. Sir Paul McCartney's estranged wife Heather Mills McCartney has been branded "greedy" and "nasty" by her own father over reports she's set to win millions from the former Beatle in their divorce settlement.

Sir Paul McCartney's estranged wife Heather Mills McCartney has been branded "greedy" and "nasty" by her own father over reports she's set to win millions from the former Beatle in their divorce settlement.