Although we tend to think of entertainers protesting a war as being a contemporary phenomenon linked to the Bush administration and Iraq, like so many other things, it's really just history repeating itself.

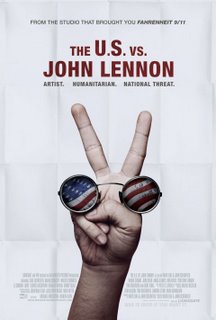

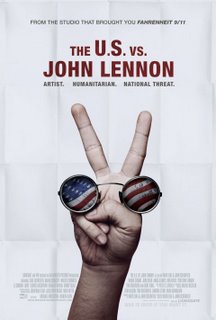

For those who have forgotten or, perhaps, are too young to remember John Lennon's passionate opposition to America's entanglement in Vietnam in the 1960s and '70s, Lionsgate's documentary "The U.S. vs. John Lennon" will come as a valuable revelation. "Lennon," which is being screened at film festivals in Toronto, Venice, Telluride and elsewhere, opens Sept. 15 in New York and Los Angeles and expands Sept. 29.

Watching it recently left me thinking that "Lennon" could score a nomination in Oscar's best documentary feature category. It's a film that's likely to resonate with older Academy members, who lived through America's tragic involvement in the Vietnam War, as well as younger Academy members, who will view it in the context of today's tragic U.S. involvement in the war in Iraq.

Written, directed and produced by David Leaf & John Scheinfeld, it was executive produced by Sandra Stern, Kevin Beggs, Tom Ortenberg, Sarah Greenberg, Tim Palen, Nick Meyer. Steve Rothenberg, Erik Nelson, Michael Hirschorn, Brad Abramson and Lauren Lazin. The film stars John Lennon and Yoko Ono and features appearances by Carl Bernstein, Noam Chomsky, Walter Cronkite, Mario Cuomo, Angela Davis, John Dean, Ron Kovic, G. Gordon Liddy, George McGovern, Bobby Seale, Tommy Smothers and Gore Vidal. It's a who's who of people who were boldface names when the U.S. government was trying to silence criticism by Lennon and Ono by deporting them. Through their comments Leaf and Scheinfeld remind us of what that period of socio-political upheaval was like and what a key role Lennon and Ono played as critics of the war.

"Lennon's" the kind of film you simply have to talk about after you've seen it, so I was happy to be able to do just that recently with Leaf and Scheinfeld and to ask them how they managed to get it made.

"John and I have wanted to tell this story for a long time, going back to the 1990s," Leaf explained. "It really wasn't until the post-9/11 world that we started to get traction, particularly in the wake of the invasion of Iraq when people at the studios and the networks started to feel that this story about something that happened a long time ago might have some contemporary relevance and resonance."

"In terms of footage," Scheinfeld added, "David and I really consider ourselves when we do these shows to be really detectives in a way, searching for the best audio-visual material. We've developed a lot of sources over the years, both domestically and internationally and we just literally scour the world looking for the best material to put in. We also preferred to use material that hasn't been seen in 10 other documentaries that have been done on John Lennon and The Beatles. So we really set as a goal for ourselves to try to find as much footage as possible that hasn't been seen before or has rarely been seen before."

"Just to give credit where credit is due," Leaf said. "John is the Hercule Poirot of the team. He is a tireless detective and does not take no for an answer. As an example, in the film you saw the footage of the day John got his green card (enabling him to remain in the U.S.). I'll let John speak to it because he's the one who did not give up."

"We'd been told for months and months and months that the footage either did not exist or had been destroyed many, many years ago," Scheinfeld pointed out. "We just kept at it. About three weeks to go before we finished the movie the footage was finally discovered in the wrong box, mislabeled in the wrong part of the news archives. But they found it and we transferred it and, as you saw in the film, it really helps accentuate what was a very critical moment in our story."

"One of the things that's interesting to me," Leaf said, "is you look closely at Yoko and it appears like she's choked up. This is a very emotional moment. We kind of take it for granted that it happened, but when you see it actually (taking place) you realize that this was a serious thing that was happening."

"And the other thing that I think probably helps define our style as filmmakers," Scheinfeld told me, "is to show don't tell. We'd heard the quote that John had given to the press that day when he was asked, 'Do you hold any grudge against (then U.S. Attorney General) John Mitchell and other people for doing this to you?' But (it was) much better to have him say it himself (in the footage that was finally unearthed)."

How do they look for footage that they don't necessarily know exists? "I think because of our history both as documentary filmmakers and our personal history as somewhat inveterate collectors," Leaf said, "we are plugged into a network of people around the world who literally have rescued these treasures through the decades as they've been discarded or displaced or dismissed from official vaults. A lot of stuff that's out there is in the hands of private collectors. So, essentially, it's sending out an SOS (that finds footage)."

"The other half of the equation," Scheinfeld added, "is we will just sort of outreach to archives all over the world where we have connections and say, 'We're looking for footage that has John Lennon and Yoko Ono in it between these years.' And we see what comes back. Oftentimes there will be some on-the-street press conference kind of footage. We wouldn't have known to specifically ask for it, but it came back to us on a whole reel -- 'Here's press conference footage' -- and then we could pick out of that what suited our storytelling."

Lennon, he continued, "has occasionally been called the most photographed man of the twentieth century. Now that could be a little bit of an exaggeration, but not by much. There's a lot of material available on him out there so we had quite a bit to look at. We probably went through more than a hundred hours worth of material searching for just the best moments for us."

The government's ongoing efforts at the time to deport Lennon (and Ono, too) is something that not everyone still remembers. "It's an episode in John's life that essentially came to define everything that happened to him after The Beatles," Scheinfeld observed. "We sort of took the point of view that people walking into the theater to see this movie, particularly if they're under 40, really don't know much about John Lennon. They know he was in The Beatles. They know he wrote 'Imagine.' And they know he was killed (in New York Dec. 8, 1980). Beyond that, there's not a lot of context to their knowledge of who John Lennon was and why he mattered. And to us this is the movie to watch if you want to know why John Lennon mattered during his life and why he matters afterwards.

"He was willing to speak to power, to stand up to power, in a way that we'd never seen a pop personality do before. It may be that his greatest work of art was his campaign for peace in terms of his post-Beatles career. He spent years and years using his fame and fortune to actually try to make the world a better place. I don't think it had ever happened before. We live in a time where everything's a reality show. John and Yoko were essentially pioneers in that, but they weren't using it to promote an album. They weren't using it to promote a movie. They weren't doing it to promote anything except peace and that's what makes them heroic artists here. And then to have the courage to stand up to the power of the United States -- the presidency, the White House, the FBI and the INS -- (shows they were) courageous artists and courageous people."

It was a little known story at the time, Scheinfeld said, and "in fact, it was really about four years after it started that the press got the first wind of what the government had been trying to do to Lennon. Some information has sort of crept out over the years. Professor (of history at the University of California, Irvine) Jon Weiner has written a book ('Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files') in which he publishes a number of the FBI documents which came out under the Freedom of Information Act and really through his good efforts a lot of what the government did is now known. But at the time it was a not a well known story.

"We're gigantic Beatles fans so we had sort of come across this story, but didn't really know a lot of the details and that's what originally got us interested back in the '90s. And the more we looked into it, the more compelling a story it became for us. We started production just a little over a year ago in July of 2005, although knowing that we were going to be doing this at some point about three months earlier (we shot some footage unofficially)."

"This is a story we've long wanted to tell," Leaf added. "I came of age with The Beatles. I was at school in D.C. during the Nixon administration. So to me this was always a fascinating story. And when you can find unknown stories about people that you think you know everything about, it's really exciting. We had kind of put our archival world on alert, if you will, that we expected to be making this movie. We probably did that about two years ago or so. Not telling them what the subject was, but just that it looked like we'd be doing a movie on John Lennon. The reason we were doing it then was that we had done what was one of the key steps in making this movie a success -- we'd gone to Yoko Ono and asked her to participate."

How did they get Ono to say yes? "We just asked," he replied. "We said, 'We think this is an important story that needs to be told.' We explained how we wanted to tell it. Her attorney's initial reaction was, 'Well, this story's in the public domain. Why do you need us?' (We said in order) 'to tell this story right and to make it the kind of movie we want it to be, we need three things. One, we need Yoko to sit for essentially exhaustive interviews. We need her to speak retrospectively for her and John and also to immerse us in the emotion of it as it was happening. We need John Lennon's music.' And we needed access to the Lennon-Ono archives because a lot of the footage that's never been seen before that's in the movie comes from John and Yoko's private collection."

"And so we knew that these were essentially storytelling elements," Scheinfeld added. "And if we were going to tell the story, we're going to do it right is our feeling or we're not going to do it."

Asked if Ono needed a lot of coaxing to get her to participate in the film, he replied, "David worked really hard to persuade her to do it. As you can imagine, she gets asked to do a lot of things by a lot of people. She's also a little bit wary, I think, and rightly so because she routinely gets blasted by the media for this or for that. So I think there's always an element of wariness. But David was the one who had gone to New York and worked really hard speaking with both the attorney and with Yoko to gain their trust and ultimately he did. And then as a partnership, as we've been working with her over the last 12 months, we've really gained her trust as she saw that we delivered the movie that we said we would. And that's been great. I think with anybody like that there's an element of persuasion that is necessary."

"We have something of a track record," Leaf noted, "of working with artists and/or their estates to create film retrospectives that tell stories in a way that bring an audience to an artist that might not have come to that artist. John's just written and directed a film about Harry Nilsson that's playing (soon) at the Mods and Rockers Film Festival. I did a film for Showtime two years ago on Brian Wilson and the lost 'SMiLE' album. We've done programs on Sinatra, Bette Midler, Jonathan Winters and The Marx Brothers. And in each one of these we tried to do two things. One was to make a film that we wanted to see. And, two, in a sense to bring an audience to things that we have passion for. To say, 'This is important to us and here's why it should be important to you.'"

"I think the other thing that distinguishes our work from our standpoint," Scheinfeld said, "is that we're storytellers. We're not just guys that go out and collect footage and slap it together and hopefully it works. We both come from the world of primetime television and know how to tell a story in a dramatic way. I think you see that in most of the productions we've done -- which is that it's storytelling. It isn't just, 'Okay in 1967 this happened and in 1970 that happened.' It's the way you lay it out."

Aside from getting Ono on board, what were the biggest challenges they faced in making "Lennon?" "I think from a storytelling point of view it was getting the right -- and this is a strange word to use for a documentary -- cast, the right on-camera witnesses to tell the story," Scheinfeld replied. "We were determined to have people in this film speaking with immense credibility, whether they were part of the Nixon administration or the radical left. Whether they were, perhaps, the greatest broadcast journalist of his time (like) Walter Cronkite or the greatest American historian ever like Gore Vidal. These are people who when they speak speak with immense context and credibility. So one of the key challenges was getting the right people to speak on camera.

"The real challenge, I think, for us as filmmakers was making sure that the film remained focused on story. There were a lot of side trips and cul de sacs that spin out of 'The U.S. vs. John Lennon' that as we got further and further into editing we just tossed out because they were taking us away from the story and so very much like a dramatic scripted film the challenge was to tell the story in a way that felt inevitable, that felt completely seamless so that when you reached the end of the movie the only way it could have ended and it all made sense and the audience feels they've gone on a journey with you in the way that all great films do."

"I think the other challenge goes back to what we were discussing before," Leaf told me, "with regard to finding material. It's one thing to sort of find generic John Lennon and/or Yoko Ono material. It was a whole other thing to find footage that really supported the story we were telling or that would have a unique resonance to the story we are telling. And we were able to do that. There's a reason why every piece of footage is in there and it does relate to the story we're telling."

"Another thing that was a challenge for us," Scheinfeld said, "was how do you score a movie about one of the greatest songwriters of the 20th Century? David and I wanted every piece of music in this film to be by John Lennon and we wanted the music to advance the story or give us some insight into what he might have been thinking or feeling at a time. That's why when in the film you hear clips from his songs, the lyrics are doing exactly that. They're moving the story forward or telling us what he was thinking or feeling at a particular moment. But then, how do you support those dramatic or humorous or poignant moments where you would normally bring in a composer? Again, because she came to trust us, what Yoko allowed us to do was to have 24 some tracks of John Lennon's solo work remixed to take out the vocals, leaving all the underlying music there. So in moments of the film where you're just hearing dramatic music, that is John Lennon music. So everything in the film is his."

"There's one Yoko song in there," Scheinfeld pointed out.

"That's right," Leaf agreed. "So we were really delighted to be able to do that and we think creatively it served our purposes and I think the film benefits from it. And I do want to acknowledge our editor, Peter Lynch, because he is a great filmmaker, too. He's got a great visual sense, but he also has a real gift for how to use music in movies. And because music is so instrumental in our documentaries we can't do it without him." Among Lynch's credits are editing "Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of SMiLE" in 2004 and editing and co-producing "Who is Harry Nilsson...And Why Is Everybody Talkin' About Him" in 2005.

In its theatrical release "Lennon" is a fast-moving 99 minutes. Looking down the road to its DVD release, I asked if there will be more content available? "Absolutely," Scheinfeld replied. "Actually, we're just finishing the bonus material. We could do the history of the 1960s from some of the interviews we got with people like (political activist) Noam Chomsky and Gore Vidal, but for the DVD we've narrowed it down to a half-dozen really interesting featurettes, if you will -- story threads that didn't make the movie."

"It's a little early to talk about the DVD," Leaf observed. "We're focused on how people are responding to the movie, itself. I buy DVDs and more often than not I watch the movie and not the bonus material. I know there's a lot of people who look forward to that, but if the movie isn't great I'm not buying the DVD for the bonus material."

With Lionsgate's solid track record when it comes to theatrical marketing, "Lennon" is in good hands as its release approaches. The film came to Lionsgate, Leaf explained, when "we sat down with our agent, Bruce Kaufman over at Broder (Broder Webb Chervin Silbermann, which was acquired by ICM in late July), and we made a list of where we thought this film belonged. And Lionsgate was right at the top of the list. Their interest was instantaneous."

"We're very independent guys," Scheinfeld added, "and that's always been our approach to work and the working environment. We had said to Bruce that we would more comfortable in a real independent type studio. So that's why Lionsgate was really at the top of the list. And really from the very first conversation they seemed to get what we were trying to accomplish here and they've really been extraordinarily supportive all the way through."

Focusing on documentaries as a genre, Leaf pointed out, "I would (mention) one thing that I think distinguishes documentaries from dramatic films. In a dramatic film the producer, the director and the actors are all working from a script. The scenes are there and then when the film goes into editing it follows the script. They move things around, but mostly it follows the script. We're sort of the opposite in a documentary. We gather all the material, all the interviews and then we assemble it much like a jigsaw puzzle. The difference being that the jigsaw puzzle you probably got from your folks when you were a kid only fits together one way. What we do could fit together 20 ways or 50 ways or 100 ways. So when we talk about us being storytellers, it's whatever gift we have that enables us to put those pieces together in a way that someone will say, 'Hey, work for me.' And that's something that's important to us."

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr/

columns/grove_display.j

sp?vnu_content_id=1003054830

Sir Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr plus the families of John Lennon and George Harrison allege that the companies fraudulently “pocketed millions of dollars” from the band between 1994 and 1999.

Sir Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr plus the families of John Lennon and George Harrison allege that the companies fraudulently “pocketed millions of dollars” from the band between 1994 and 1999.